The LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Collaboration published a new, more accurate, test of Einstein’s theory of general relativity using their clearest gravitational wave signal yet: GW250114. In all tests, the observations match the theory’s predictions.

Since its publication, over one hundred years ago, Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity has revolutionized physics and our knowledge of the universe, and testing its accuracy in different scenarios has been a fundamental mission of experimental physics. Researchers of the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Collaboration have just published an article in which they provide some of the most precise tests of Einstein’s theory of general relativity to date, using data from the binary black hole signal GW250114, the clearest gravitational wave detected to date.

The clarity of this signal allows for researchers to obtain very accurate information about the event that generated it, and the parameters of the signal itself. This had already proven valuable when in September the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Collaboration published research that confirmed Stephen Hawking’s black hole area theorem using the data of this same gravitational wave signal. This time GW250114 was used to study the predictions of Einstein’s general relativity, looking for any deviation from it that could hint at new physics that goes beyond what we know today.

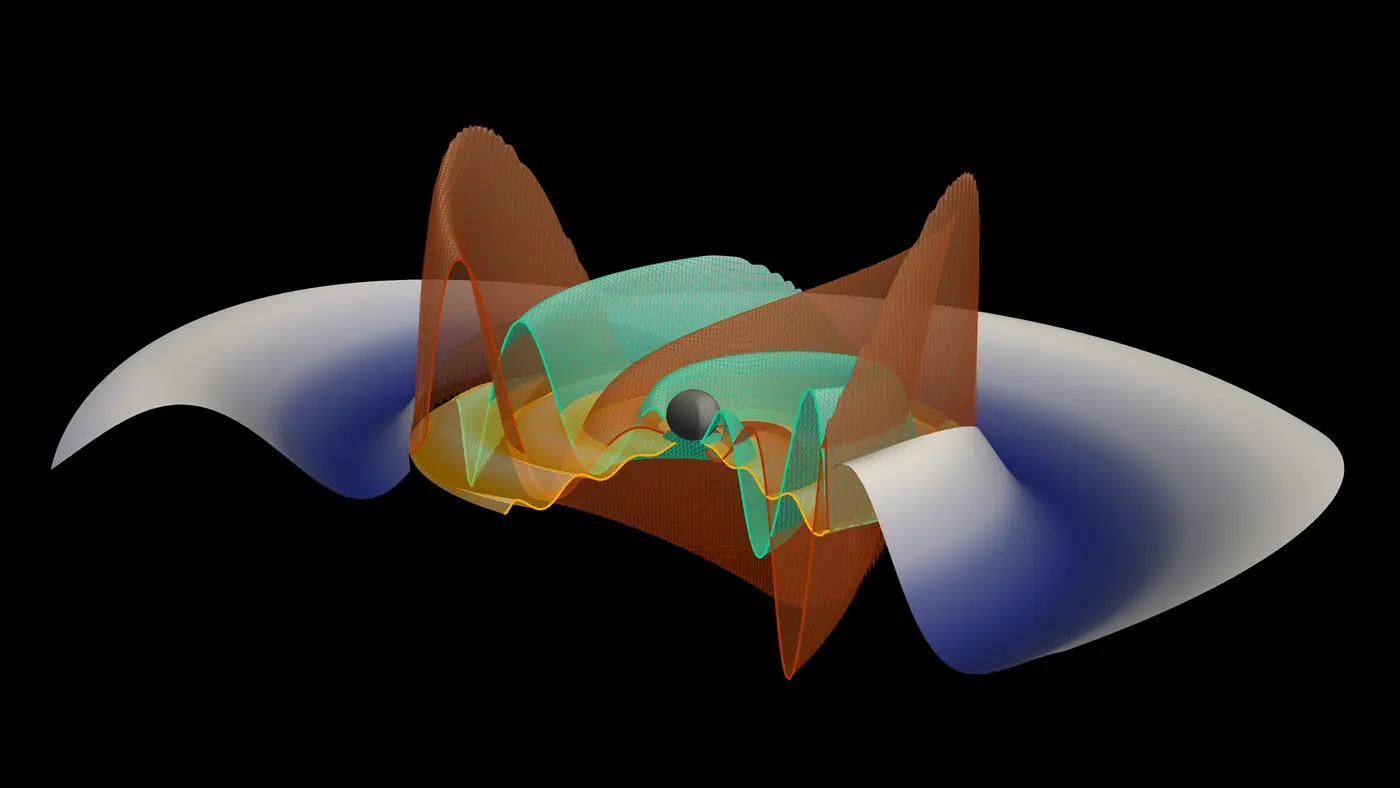

The international research team obtained some of the key results using a method known as black hole spectroscopy. The research focused on the ringdown of the GW250114 signal – the phase when the black hole settles into its final state right after the merger – and the characteristic spectrum of gravitational-wave modes, or tones, emitted during this phase.

“When two black holes merge, the collision rings like a bell, emitting specific tones characterized by two numbers an oscillatory frequency and a damping time.” said Cornell University physicist Keefe Mitman, who co-authored the study “If you measure one tone in data from a collision, you can calculate the mass and spin of the black hole formed in the collision. But if you measure two or more tones in the data – which a clear signal such as GW250114 allows – each of those is effectively giving you a different mass and spin measurement, according to general relativity.

“If those two measurements agree with one another, you are effectively verifying general relativity,” Mitman said. “But if you measure two tones that don’t match up with the same mass and spin combination, you can start to probe how much you’ve deviated away from GR’s predictions.” GW250114 was clear enough for the researchers to measure two tones and constrain a third. All agree with Einstein’s general relativity.

“The idea is that analysing the different parts of the signal should produce consistent results if General Relativity is valid and our models are sufficiently accurate,” said Jacob Lange of the National Institute of Nuclear Physics – Turin Section, another co-author and analyst of the project, “for GW250114, we did obtain a result consistent with GR with unprecedented accuracy. This was due to the spectacular intensity of this signal. In the future, these louder signals will become more and more common. If deviations from GR exist, these signals will be the window through which we will discover them.”

“These techniques offer a unique probe of gravity in its most extreme regimes, revealing information from the spacetime in the immediate vicinity of a black hole. As such, they are an invaluable tool for advancing a wide range of topics in fundamental physics through observations.” said Vasco Gennari, PhD student and analyst of the project at Laboratoire des 2 Infinis in Toulouse. “Future observing runs at higher sensitivities will further reduce uncertainties in these measurements, strengthening our ability to validate such tests and, for the first time, allowing us to challenge other predictions of the black hole spectroscopy program. This milestone crowns decades of research in this field, yet much work remains to fully characterise this deceptively simple regime.”

Image credit: H. Pfeiffer, A. Buonanno (Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics), K. Mitman (Cornell University)

The LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA Collaboration

LIGO is funded by the NSF and operated by Caltech and MIT, which together conceived and built the project. Financial support for the Advanced LIGO project was led by the NSF with Germany (Max Planck Society), the United Kingdom (Science and Technology Facilities Council), and Australia (Australian Research Council) making significant commitments and contributions to the project. More than 1,600 scientists from around the world participate in the effort through the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, which includes the GEO Collaboration. Additional partners are listed at my.ligo.org/census.php.

The Virgo Collaboration is currently composed of approximately 1.000 members from 175 institutions in 20 different (mainly European) countries. The European Gravitational Observatory (EGO) hosts the Virgo detector near Pisa in Italy, and is funded by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France, the National Institute of Nuclear Physics (INFN) in Italy, the National Institute of Subatomic Physics (Nikhef) in the Netherlands, The Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) and the Belgian Fund for Scientific Research (F.R.S.–FNRS). A list of the Virgo Collaboration groups can be found at: https://www.virgo-gw.eu/about/scientific-collaboration/ More information is available on the Virgo website at https://www.virgo-gw.eu

KAGRA is the laser interferometer with 3-kilometer arm length in Kamioka, Gifu, Japan. The host institute is the Institute for Cosmic Ray Research (ICRR), the University of Tokyo, and the project is co-hosted by National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) and High Energy Accelerator Research Organization (KEK). KAGRA collaboration is composed of more than 400 members from 128 institutes in 17 countries/regions. KAGRA’s information for general audiences is at the website gwcenter.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/. Resources for researchers are accessible from gwwiki.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp/JGWwiki/KAGRA.

Contacts

Via E. Amaldi,5

56021 Cascina (PI) - Italy

Tel +39 050 752511

Contact us

How to reach us

Stay Tuned

EGO is a consortium of